Radio Caroline-a 40 year anniversary

It was 40 years ago in 2004. As on Easter Friday,

1964, the first transmissions went out from the radio ship mv

Caroline(Fredericia) off the UK Essex Coast on 1520 kcs, 199 metres. A most decisive

event in Northern European broadcasting. Almost 4 years later, the original

Radio Caroline had come to a sad end. Here follows a series of material related

to this incident, to serve as our tribute to The Lady of the airwaves.

The end of the original

Radio Caroline

1. Introduction adapted from

”The final curtain”, an essay by Tim Davies, The Research Officer of the former FRA,

Free Radio Association.(Spotlight, 1970[1].)

The

Radio Caroline South ship (Mi Amigo} in dry dock at the Orange Wharf,

Amsterdam, on March 17th, 1968. Picture:Unknown

After the departure of the other offshore stations

after 14th August, 1967, Radio Caroline found herself alone and uncertain of

her future; Insufficient revenue was pulled in from advertising to run the two

ships; the Mi Amigo (Caroline South) and the Fredericia (Caroline North).

Between 14th August, 1967, and the close-down on 3rd March, 1968, there were

less than half a dozen paid advertisements. Most of the advertisements heard on

the two Caroline ships were taped from television or from other radio stations,

and of course there were

always the old pre-August 14th casettes to rely on.

As far as is known, no very great effort was made to

obtain advertising from abroad. Radio Caroline relied on "plugged" records

to finance the running of the ships. Each ship cost approximately £1,000

per week to run and various groups and record companies paid £100 per

week for 30 plays of their nominated record. There was delay in getting money

out of the country, and large debts began to accumulate in Holland. The biggest

debt was to the Offshore Tender and Supply Company, which was a subsidiary of

Wijsmuller, a large Dutch tug firm.

Eventually the tender company refused to let the

account grow any larger. On Friday afternoon, March 1st, a meeting was held in

the company's office, and it was decided to tow the ships into Amsterdam. No

one in the Caroline organisation from the boss, Philip Solomon, to Nan

Richardson, who worked in the Amsterdam office, had any prior knowledge that

the ships would be towed away early in the morning on Sunday 3rd March, 1968.

The Mi Amigo arrived in Amsterdam on March 4th, and

the Fredericia (also known as the MV Caroline) on March 9th. Both ships were

dry-docked upon arrival. At time of writing the ships are still in Amsterdam,

subject to the decision of a court hearing which started as long ago as 27th

February, 1969.

There have been various attempts to re-start Radio

Caroline. One such was from the former Radio 270 vessel, Oceaan 7. There have

also been numerous rumours that Caroline would return on such and such a date.

My personal opinion is that there is very little chance that Radio Caroline

will ever be heard again.

2. How the Mi Amigo was silenced

by Andy Archer

From Spotlight, Free Radio Association 1970

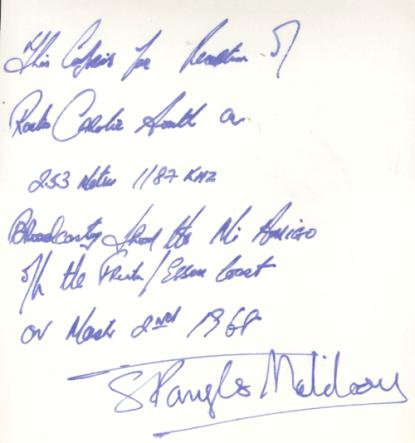

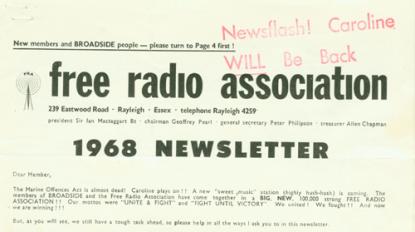

Vintage brochure from the FRA 1968

During the past year, I've read so many different and

conflicting stories about the closure of Radio Caroline that I feel it is about

time you were told the truth. And one of the few people who can tell you the

truth is me, because I was on the Mi Amigo when she was towed away; Honestly; I

would rather have kept the real truth to myself and to the other fellows who

were on the ship with me, namely Roger Day, Stevi Merike, Johnnie Walker and

Bud Ballou (Henry Morgan and Carl Mitchell were on shore leave); But probably

we have kept our secret long enough, and I would rather you know the true story

than have lies told you by someone who was not even involved.

On March 3rd 1968, at 2 a.m., I finished the Carl

Mitchell show and wished the

listeners goodnight, and hoped they would join us

again at 5.30 a.m. for the Roger Day show; Johnnie, Stevi and I then went to

the mess to drink coffee and chat with "Harry the Mouse", our

favourite character amongst the Dutch crew; We all retired to bed at about 4

a.m. Just one hour later the duty engineer. Ray Glennister, switched on the

transmitter; He also switched on the Ampex tape machine to play segway music

until Roger arrived at 5:30 a.m. But before this could happen, the tug, Titan,

pulled alongside; At 5:19 a.m. the captain of the tug walked into Studio 1, and

told Ray to switch off the music because we were to be towed back to Holland-

Ray obeyed, and then woke Johnnie who in Henry Morgan's absence was the senior

disc-jockey; They were given 15 minutes to clear the cassettes and records out

of both studios before they were locked up; At approximately 7:30 a.m. we

started to move towards Holland; All the DJs were now up and wondering if this

was the end. The weather was very bad with visibility no more than 800 yards;

We had no hope of getting a signal to England to warn our boss, Philip Solomon.

We had nothing to do on the journey except eat, sleep and play cards;

Throughout the afternoon we tuned to the BBC and to Radio Veronica, but there

was no mention that we were moving back to Holland nor even that we were off

the air; I do understand that in his show the following morning Tony Blackburn

included a rather sarcastic comment about the proceedings, namely a welcome to

his new listeners. We arrived in Amsterdam at 5 a;m; on 4th March, and were met

by Robbie Dale, his girl friend Stella, and Nan Richardson, the wife of our

chief engineer who looked after the Amsterdam office; Bud Ballou and Johnnie

Walker stayed on the Mi Amigo as duty DJs: Roger, Stevi and I went to the

office and after a hectic cat and mouse gamearound Amsterdam with reporters, we

flew to London and went our separate ways;

All the DJs received a cheque and a short note asking

us to keep in contact; Nothing further happened, and so ended the life of a

fantastic station. Radio Caroline: May she never be forgotten; I hope too, that

no one will forget her founder Ronan O'Rahilly.

Well, that's the true story of what happened: The last

record ever played by Radio Caroline was "Cinderella Rockefella" by

Esther and Abi Ofarim; The station then

closed down with its theme song, "Caroline"

by The Fortunes: I have the actual record in my collection, and I wouldn't swop

it for anything.

3. From Happy Birthday Radio Caroline 20 years old

Easter 1984.

(Produced by Monitor Magazine, which

was an

unbelievably detailed fanzine produced by Roland “Buster” Pearson

of Benfleet in Essex with loving care until his death. I was proud to subscribe

to it.)

Introduction by the late Roland

”Buster” Pearson.

A little over six months after the MOA a comment was

made on Caroline South that the station may be off the air the following day as

some work had to take place on the generator. It was an innocent remark, no one on board at the time knew

that Caroline South and North would be off the air for a much more sinister

reason. For the next day was

Sunday 3rd March, 1968. At 2 a.m.

Andy Archer closed down Caroline South; three hours later the duty engineer,

Ray Glennister, began to play a few records in preparation for Roger 'Twiggy'

Day's programme. Roger was unable

to begin his programme at 5.30 a.m, however; a tug had arrived alongside and

before anyone knew what was happening the Mi Amigo's anchor chain had been cut

and she was under tow. Off the

Isle of Man, the Caroline was suffering the same fate. A double act of piracy

had finally silenced Caroline North, and forced Caroline off the air for what

turned out to be four years, six months and twenty-six days.

“The shop with the bell in the

window”. Caroline North’s Liverpool office in 61 Lord Street was

advertised this way on “199”.

The following is a transcript of an

interview(transcribed by KIERAN MURRAY) which took place in the Radio

Carousel(AM 1386 kcs) Studios in Navan, County Meath, Eire, on Tuesday 11th May

1982. The programme presenter was

Pauric Welsh, and the guest

DAFFY DON

ALLEN

P.W:

If there's a distinctly Country flavour to the show tonight, then you

will know why when you meet my guest for the evening. He was born in Canada, of Rumanian parents, he worked in

radio in both Canada and the United States. He came over this side of the Atlantic in the mid-Sixties to

work on the High Seas as a DJ with Radio Caroline, presenting what they called

"The Biggest Country Show This Side of Nashville". I know you've already guessed his name,

because he has just become the newest voice on Radio Carousel here in Navan, he

is of course DAFFY DON ALLEN, or DON ALLEN to us. Don, you're very welcome to this programme!

Don:

Thank's very much indeed Pauric, it's nice to be on the show.

P.W:

How did I do for the beginning, is that an accurate description?

Don:

Yes, very accurate indeed.

P.W:

Now how did it all begin for you?

Don:

Well, I always look back at it in retrospect now; there's a song that

Gene Stuart - who is a very good Irish singer - came out with, the song was

called "I'm just Lucky I Guess", and you know, since I heard that song,

I sort of look back as the years go by - seventeen in all - I came over for a

holiday, and at the same time

before coming over to England for a holiday, I was

working between radio jobs. I was

working for a firm known as Canadian National Railways, and coming back from

Winnipeg one time to Vancouver, I picked up this old copy of Weekend Magazine -

you know these colour supplements that you get out of newspapers - and there

was a very interesting article about this ship, broadcasting from the High Seas. I thought, why over in Europe do they

have to broadcast from ships? I

just couldn't understand why these people were broadcasting from a boat. It

seemed totally senseless. At the

time, as I'm sure everybody appreciates, radio was state-controlled – even

Radio Luxembourg. There was no

such thing as Commercial Radio in the sense. But I didn't realise this, because I took Commercial Radio

for granted, being a Canadian and having travelled extensively throughout

America. I could not grasp this,

that radio was not commercial over in Europe. I had not even been to Europe.

Anyway, I had saved a few dollars and decided to see

Europe - Paris, London and places like that. I came over here and consequently pure professional

curiosity led me to CAROLINE HOUSE.

To cut a long story short - I went up to London one

day and I walked into Caroline House and there was everybody and everybody

there. I walked up and said to the

receptionist ”Good afternoon, I'm a Radio Announcer from Canada, could I

see the set-up?” She said

"Are you a Disc Jockey?”

I said 'radio announcer'.. We didn't use the term DJ in Canada at that

time, however, we sort of came to a conclusion that a Disc Jockey was an

announcer and an announcer was a Disc Jockey. Next thing I knew, this Programme Director of the South

(Caroline) Ship came up to me and said "you work in radio?" I said "Yes". He said ”would you like a

job?”And I said ”Are you having me on?"

Anyway he interviewed me - I didn't do an audition

– and, to cut a long story short again, next day I was on a ship called

the "Mi Amigo" which was bobbing up and down like a cork in water,

off the Frinton-in-Essex coast. I

had never been to sea in my life and that was the beginning of my radio career

on the sea.

I don't think Caroline had reached its peak yet. There were people there - unknown

people - but very dedicated people, who were yet to be discovered. Names like SIMON DEE, TONY BLACKBURN -

I remember him very well. In the

early days he was known as Tea Cosy, because his hair resembled one!

P.W:

But did he still tell those inane jokes that he tells now?

Don:

No! He got that idea from

various Disc Jockeys and blended them all together. He got that from a DJ known as KEITH SKUES, who now is Managing Director of a radio station

in Yorkshire. England. Keith was a

very intelligent announcer and a very witty announcer and of course Tony

Blackburn took his style.

He was a good DJ, but I think he had his good looks

and the fact that he was the very first voice in RADIO ONE helped him

greatly. No disrespect to him,

though.

I knew Tony when people didn't know Tony... he didn't

even know how to cue up a record when he was on CAROLINE SOUTH . Then he went to RADIO LONDON and said

that he owed everything he had achieved in radio so far to Radio London, but

Tony also owes everything to RONAN O'RAHILLY and Radio Caroline.

P.W:

Before we got on to Radio Caroline itself, tell us something about Simon

Dee, because I remember seeing Simon when he had made it very famous on

television in England.

Don:

As I said about Tony Blackburn, he was young - only in his teens at the

time - and he had his looks going for him. Now Simon Dee had had a gimmick going for him, he was

officially the first voice to be heard on Caroline. Simon was a very easy going

bloke, I think success got to him too quickly. Like the Beatles, you know? The Beatles were just instantly discovered and suddenly

BOOM! Success overnight and it was

too much to handle. They tried everything - they went to India, they tried

meditation and all this... well Simon, being the first voice on Caroline had

that gimmick going for him. After

he left Caroline he went on to Radio Luxembourg, then he went on Radio Two and

then he had his own television show.

Everything just fell out of the sky for him. Everybody who has been on

Caroline has been very fortunate; that I can remember. I can name names – Tony

Blackburn, Simon Dee - they are just two.

Success just rained out of

the sky for them. They didn't go

seeking it. I don't believe that

Simon was seeking a job on 208; I think 208 were after him. The same as BBC

Radio Two-then the Light Programme - and his television programme, everything

just fell into place. This all happened because he was the first voice on

Caroline.

P.W:

Of course you worked with TONY PRINCE as well?

Don:

Tony? Oh I remember Tony in

the old days when he had his Oldham "Eee-ba-Gum" accent, you

know. I've still got some of his

tapes. Tony sounds very polished now...

he's extremely polished... he's been with Radio Luxembourg now for about

fourteen years. But when Tony

arrived on Caroline in the early days, he was, well, the only thing missing was

his welly boots and little flat cap!

He was straight out of Oldham.

But his heart was in entertainment. It seems small people are always more determined than bigger

people, and Tony did great. He wasn't accepted entirely at first, but

eventually he was accepted. He was

sent down to the South Ship to newsread... that was totally out of his depth..

this wasn't on. Tony just wasn't a

newsreader. He was a Disc

Jockey. An exhibitionist. An extrovert.

P.W:

To put it bluntly. Don, what was it like out on the middle of the sea,

playing records?

Don:

It’s not the first time that question has been asked. In fact when

Caroline got towed away, I was offered a substantial sum of money by a Sunday

Paper to disclose the 'gorey' side of Caroline. And I couldn't do it. I didn't even think about it. The journalist, when he heard my reply,

thought that everybody has got their price to pay, but I still refused. I spoke to Radio Caroline Boss Ronan

O'Rahilly about it and he said well if you can live with your conscience, go

ahead. I still refused to do the

newspaper interview.

The station was very unorganised in some aspects, but

I'll give you an amusing instance.

In its heyday, Radio Caroline it was just bristling with success, no

matter which way you looked at it.

The agencies were clamouring, queueing up, to advertise on

Caroline. Caroline House was in a

very posh part of London, and there were so many people walking about that one

did not know whether these people were working for Caroline, or whether they

were just browsing through. Now I

can remember one chap called JIM MURPHY-MURPH THE SURF. His wife was sitting in

the foyer, waiting for him in Caroline House. The two directors ALLAN CRAWFORD who owned Radio Atlanta and

Ronan O'Rahilly who owned Radio Caroline - had a fall out or something, and

when Allan came down, he was in a foul mood. He actually sacked Jim Murphy's wife, who was waiting for

him in the foyer. She wasn't even employed at the station! But he just took it that everybody in

that house was employed by Caroline.

P.W:

Well, I wasn't looking for the sordid details, Don; all I was really

looking for was details about the ship!

Don: Well, put it this way, we were well looked

after. The food was good. We had duty-free cigarettes. Booze was there... it was all duty

free. It was as if you were in a different

country. The only thing they

didn't do when you came off the

ship was stamp your passport. But

they would go through your suitcase, and if there was anything you took out,

like, say, an expensive tape recorder, radio-, jewellery, or anything like

that, you had to declare it in the customs hall, in Ramsey, Isle of Man, Otherwise, you were bound to pay duty

when you came back in. Why, I

don't know, because technically speaking it was as if you were going to another

country. Even the laundry notes had to be triplicated first.

Life actually on the ship... a lot of people, first

thing they say, was there any women on the ship? There was never any women on

the ship... we lived, breathed, and slept radio. Three years on Radio Caroline was the equivalent to nine

years on any ordinary radio station, because when you take on average, you work

one third of the day; the other one third of the day is leisure and the other

one third is sleep. We were

spending three thirds of the day on Radio Caroline.

P.W:

Well, did you find it boring or... ?

Don: No! Not at all! I don't think I would have been there for three years. I would have been off after the first

couple of months... I was dedicated to radio. It was one of the most exciting things that ever happened to

me.

P.W:

And of course, you did two weeks on two weeks off?

Don: Well, originally on the South Ship in early '65,

it was two weeks on, two weeks off, with pay. The pay was exceptionally good for that particular

year. I spent March, April. May,

June. I came off the South Ship

and was all set to quit Radio Caroline because of health reasons; I just

couldn't stand the sea. Then I was

offered this job in Caroline House itself. I took this from June until September or maybe November

1965. Then they asked me if I would go on the North Ship just as a temporary

replacement, because a few of the lads had shifted about. TOM LODGE had gone to Luxembourg. Lo and behold, I agreed to it -

reluctantly. I went up on the North Ship and there was only one person left on

the ship to carry on broadcasting.

BOB STEWART was the only one.

So between us we kept the station going-- just the two of us.

P.W:

It sounds like crisis point!

Don: It didn't seem a crisis point. That's the joy of it.

I suppose when you have this type of dedication one

doesn't count it as work. But

let's move on to your own personal life.

Say, during Caroline. You

were in the public eye in Britain or certainly the public ear. Did your own life change because of

this?

Well, I tried my very hardest not to be in the public

light when I was off the ship, because later on when I made up my mind that I

was going to stay on the North Ship, when we got off, I thought to myself that

one week out of three you've got to yourself. And after being on a ship for two weeks... I mean some

people, like Tony Prince, liked doing gigs. I didn't. I

just wanted to sit back and relax; go to places and, sort of, not be

known. I love to entertain people

behind a microphone, but I think I would have been lost on stage.

P.W:

Yes. but you must have got the fan mail?

Don: The fan mail? Oh golly! In

fact they had to start a fan club.

I found it totally impossible to adequately and accurately answer the

letters. One lady in Yorkshire

offered to start a fan club for me and I thought this is a good thing. So I gave her an answer to all the

general questions that were asked.

Generally it was just radio questions... what was it like on the ship?

etc. Generally it was just radio

questions. People used to write

and say how lovely the boat looked... Tony Prince was one of the biggest

offenders as far as exaggerating and stretching details. He used to tell people that we had

waiter service out there-things like this!

The crew on the ship were Dutch. We had to adapt ourselves to Dutch

food. You were well looked after.

The food was exceptionally good, because food was the main thing. We got paid after enjoying ourselves

for two weeks! The overall

atmosphere on the ship was very, very good. That is the Radio Caroline North Ship.

On the South Ship there tended to be a lot of

megastars down there. Ones that

... sort of... made it... let's put it that way. However, there were people on the North Ship that made it

too, like Bob Stewart, who is on Luxembourg now. Tony Prince - he's on Luxembourg. That's two. Then of course you have DAVE LEE

TRAVIS, who was on the South Ship.

Radio Caroline South was aimed at a specific audience,

the South of England - London primarily was their target. Whereas on Caroline North we were just

the North. You know, people

writing from Scotland, the North of England. Ireland. I remember getting a lot of mail from the South of Ireland -

in fact a lot of people that

I have met since I came over here in January (1982)

were teenagers at the time. They

are now married. They have children of their own and

they say "I remember you from Radio Caroline”.

P.W:

Honestly, we could stay talking about Caroline all day; I've got so many

things to ask you, Don, we might have to do two or three shows. Tell me, were you very sad the day She

was towed away?

Don: I was on board. It was the saddest... I sensed it... I'll try to keep this

as short as possible because this could get very sad. Have you got any Kleenex? Actually; we were not closed down

by government legislation. A lot

of people seem to think that we were closed down because of the legislation

that was introduced. I will briefly

go into why we were closed down and try to keep it as short as possible.

Radio Caroline North and South were being tendered -

looked after - by a Dutch tender company, they sold us food, men to look after

the ships, and oil to run the ships.

After the Bill was passed, Caroline, I believe, was leased out. I won't go into detail there but

anyway, to cut a long story short... and be as brief as possible about this.

Radio Caroline continued to carry on broadcasting after September the

first. It was outlawed - rather

legislation was passed against it -

on the fifteenth of August down in the South. All the offshore stations and the Forts were legislated

against on the fifteenth of August. The one exception was Radio Caroline

North. Legislation was not passed

on us until fifteen days later. We

were given a fifteen day reprieve - it was passed at the end of August,

thirty-first of August - midnight.

Caroline was legislated against not only by England, but the Manx

Government. You see, we were off

the Isle of Man. This is a very,

very delicate situation, which is another story in its own right. However, the Isle of Man, feeling that

after approximately four years of free publicity, which they would have had to

pay thousands of pounds for, they were not happy about Caroline being outlawed.

After midnight, thirty-first of August, all the surviving

ships that were on the High Seas ceased to broadcast - apart from Caroline

North and South. They were the

lone survivors. Radio Caroline

continued to broadcast and it was on the fateful evening of March the first, I

believe, that both Carolines were taken away by the Dutch tender company. Let me make that quite clear. Caroline South and North were not

closed through legislation. They

were towed away because of unpaid bills for oil, men and food. And as a result of that, the chains

were cut, both ships were towed into Holland and there was every possibility

that these ships could have come back, had the bills been met; the bills were

never met. Therefore, the two

Carolines began to rust in Amsterdam.

The North Ship was broken up for scrap. The South Ship - there were a lot of

Free Radio people determined the South Ship was going to survive. And in later years, the South Ship was

taken out of harbour, back out or to the High Seas.

The end of Caroline was because of unpaid bills and

NOT government legislation. The

day that we first got wind of this, I saw this very powerful tug. It landed a couple of days before they

actually came over to the ship; they pulled into Ramsey (Isle of Man). They were in constant communication

with Holland by Short Wave Radio and they were told when to cut the anchor

chain. It happened on a Saturday

evening. I had just finished my

Country Show. We went off the air

at ten o'clock and we watched a bit of television - myself and a few more

fellas - and about two o'clock Sunday morning, we were all set to go to bed

when we heard this 'thump' on the side of the ship. We all thought, what could that be? -I had it in the back of

my mind that it could have been this tug.

Apparently men from that tug had come across and had taken over our

ship. They had pirated it. We were sort of victim of our own

fate. They said they had their

orders to out the anchor chair and late Sunday afternoon we were towed

away. It took them a whole day to

cut the anchor chain, it was that powerful. We were towed away - and we were on the High Seas for a week

- the North Ship was, the South Ship was towed overnight into Holland. The North Ship was towed all the way

down the coast of England and consequently a week later we landed in Holland. The ironic thing about it - if I may

point this out - I started on

Radio Caroline on March the Eighth, 1965. I last stepped off the ship on March

the Eighth, 1968. - And a year to the date, of that day, I started on Manx

Radio. March eighth is a very,

very critical day for me, believe me!

P.W:

Now, Don, when you were finally let off the ship on March the eighth,

where did you go from there?

Don: Well, I was out of work in radio for exactly a

year. In that period, I did, I

think, one show, which will I remembered by a lot of people. It was called the CAROLINE REVIVAL HOUR

and this was on RADIO ANDORRA, which I recorded in a Paris studio. This went on over the airwaves of

Andorra, with the intention that they were going to do a lot of this, but the

reception in England, unfortunately, was not as good as they had hoped it would

be. It got press coverage. things

like this. I had to quickly do

that before I took up my position as Programme Controller of Manx Radio. I arrived there a year after the day I

stepped off Caroline. That's when

I started working for a living.

Being towed away

South Ship by Stevi Merike.

From an interview by BOB RENDLE in Disc and Music Echo

also from Happy Birthday Radio Caroline 20 years old Easter 1984 produced by Monitor

Magazine.

Wijsmuller decided that they were going to tow the

ships in and of course we knew nothing about it which was always the case. They sent off their little tugs, closed

the transmitter down and locked the studio door, put the rope aboard and away

we went. Nobody knew what was

going to happen. It was a very misty Sunday morning and nobody on land knew

that we’d gone. The first

indication anybody had that we’d disappeared was when we passed the

lightship which was about twelve miles to the seaward of us. They radioed back

to North Foreland Radio that the Caroline ship had just passed them and

that’s the first anybody knew.

The trip back was very slow; it wasn't a particularly

rough day. It just took the tug a long time to tow us back to Ijmuiden and via

the trans-Nederland canals to Amsterdam harbour; to the wood harbour. It was about three o’clock in the

morning by the time we actually got into Amsterdam.

Thanks to Andy Archer the trip was quite hilarious

really; because he camped it up the whole way. I think if he hadn't been there it would have been very;

very depressing.

I thought the idea was that eventually whoever was

owed the pennies would get their pennies and we'd get towed back out again; but

the British owners decided 'sod it', you know? Ronan O'Rahilly was just a figurehead; I don't think he was a director; I

think he left the board in 1965.

When

Caroline went off the air we were all thrown into poverty and obscurity; with

the exception of Robbie Dale who stayed in Holland and went on TROS Radio. For the rest of us it was a very lean

time. I had to get a job because I

was married and our first baby was on its way; so I went and worked in a

hearing-aid factory; which was dreadfully depressing. Then one day I happened to be talking to Richard Swainson

who used to be the publicity man for Caroline and Radio London. He told me Screen Gems Colombia were

looking for someone to hock their music around the BBC. So I

went up there; they took me on; and I got back into the music business.

North Ship By Greg Bance

From Happy Birthday Radio Caroline 20 years old

Easter 1984 produced by Monitor Magazine.

Since

Radio 390 had closed down on 28th July 1967 I had done practically

nothing. It was one of the

extremely rare times when I had no work at all. I hadn't really considered Caroline as being an option after

August 1967; mostly because the station sounded pretty ropey and it was all

plug records. But by about

February 1968 I was getting fairly desperate to do some kind of radio work

again.

A friend and colleague; Alan Clark; was also looking

around and it was he who had the idea of going along to Carolines office -

well; it wasn't really Caroline's office; it was Major Minor records. He saw Jim Hoolighan; who was something

to do with Major Minor and something to do with Ronan O'Rahilly; he used to

keep Ronan's unwanted guests at bay I think. He didn’t want any experience or audition tapes; he

just said ”When can you start?” In fact Alan was offered a job on the South Ship and I was

offered a job on the North Ship. For some reason Alan never got as far as the

South Ship; I think they'd closed down by the time he was actually going out

there.

Three or four days after seeing this Jim Hoolighan

fellow I went off to Dundalk; I went there on the Saturday

because the tender was due to go out on the Sunday; but in fact it didn't. I bumped into Fred Bear who was RWB on

Radio City and Ross Brown on Radio 390. Australians as you know always wear

shorts be it summer; winter; anytime; he always used to wear these infernal

shorts. We filled the next few

days going to places like Dublin...

Eventually we left to go out to the boat mid-evening

on Tuesday night. It took all

night and most of the following morning to get out to the Caroline Ship, which

was anchored off the Isle of Man; and it was an extremely rough night. When we

first went on the tender Ross Brown said ”Let's go on the Bridge”,

everybody else seemed to be on the Bridge for some reason; I never did discover

why. I didn't want to go on the

Bridge; I wanted to go to bed; which is what I did:

I found myself a bunk; but I didn’t sleep very

much. We got to the Caroline about

mid-day I suppose. It was a grey,

nasty day, rough sea, raining, very unpleasant.

The only connection that I had with Caroline at that

stage was the fact that Martin Kayne was there. He had worked for Radio Essex a couple of years previously

as Michael Kayne; so I knew him; but he was going off on shore leave as I

arrived. I was going out there

with Ross Brown; and coming off the boat were Martin Kayne and Jason

Wolfe. There apart from Ross Brown

(or I should say Fred Bear) and myself, Jimmy Gordon - an Australian guy, he's in Adelaide now. Don Allen; of

course; and Lord Charles Brown; more usually known as Lord Charles Brown than

Charlie Brown. People used silly

names on that ship; I don't know why.

I was plain old boring Roger Scott - I should say the first plain

old boring Roger Scott -at that time.

I can't remember much about the engineers. The cook was a Dutch guy, so we had the usual Dutch food,

which was Wonderloaf and pickles and soup. The food was quite good actually, as far as Wonderloaf and

pickles and soup goes, it was only the-best type.

Jim Gordon promotional card. A gift from the late

“Daffy” Don Allen.

The initial impression of the Caroline boat was

delapidation basically, although inside it was a different story-it was fairly

well appointed. The most

eye-catching part of the boat, in a rather poetic way, was the staircase! It

had been a ferry in Scandinavia, so the ordinary passengers wouldn't climb up

and down ladders, they had to have a stairway; and it was a sweeping stairway,

the sort of thing you have in Capital Radio. I had the cabin at the bottom stairs, which was the DeLuxe

Suite actually, built-in sanitary facilities en suite. Which was quite unusual for an offshore

station.

The most noticeable thing about Caroline North from my

own personal point of view was the fact that it was the least friendly station

I worked on. It was fairly

soulless, a bit disappointing actually.

Had I worked there longer perhaps I would have got to know people

better; but it was a station very much of individuals. There wasn't much of a team

spirit. It seemed to me that

everybody was just passing their time, knowing that the station was eventually

to close. We didn't know it was

imminent but we knew it was going to happen sometime, so there wasn't a great

feeling for the station.

Initially I was given news to do, which came from Manx

Radio. So I was doing news during

the day Wednesday afternoon; Thursday and Friday, then Saturday I did my first

and only programme. I did six till

eight in the evening I believe.

Had it been a weekday my voice would have been the very last to be heard

on Caroline North. However, that distinction evaded me because being Saturday

Don Allen did his Country and Western Jamboree, so he closed at ten- and that,

as is well known, was that.

The following day the boarding party, the people who had

come to take us away, arrived early in the morning. I hadn't detected anything

being in the offing, during those few days I had been there I never heard

anybody talk about the possibility of it happening. Yes, things were a bit decrepit, but people had been paid on

time; the

records were there so we presumed the record companies

were paying for their plug records.

Things seemed to be carrying on in; for offshore radio, a fairly normal

way.

I missed them actually coming on board. I was asleep. I was awoken by one of my colleagues, I think it was Don Allen, and went up

to find out what was going on. There had been no nastiness as far as I could

gather. They stated what they were

there for, it was quite obvious they had come to keep the station off the air,

quite obvious they'd come to tow the ship in, they took the crystal out of the

transmitter and there was nothing much we could do about it. I don't think they'd met with very much

resistance because I'd have heard about it had they done. I’m sure there's

not any drama or anything deedy, but it was all very matter of fact and really

quite mundane.

We left the anchorage on Sunday evening and of course

all the people on board at the time stayed on board until the boat reached

Amsterdam. We didn't feel like

hostages or anything like that. It

was all very amicable. They lined

in with the cardgames and the drinking and the eating; it was just a larger

crew than usual, that was the only

acceptable difference. One of the

crazy things about offshore radio is you tended not to worry about things that

I would do normally. Even in the

roughest conditions I don't think any of us ever worried about personal danger.

I basically went there for a bit of adventure so whatever happened that was

adventurous was a bit of a bonus.

It sounds kind of romantic sailing from the Isle of

Man round the country by way of the Lleyn Peninsula, Cardigan Bay, Lands End,

English Channel to Amsterdam, but there really wasn't anything spicy about it,

it was more boring. It was a week

of quite rough seas, not very much happened; most of the time I remember lying

in my bunk looking at the porthole getting soaked and occasionally some water

would come in. It was not a

particularly exciting time. I think it was noticeable there were no hoards of

weeping girls waving their knickers at us. This had been the case, we had

heard, on Radio London when the Marine Offences Act came in, but we went in the

mouth of the canal that leads to Amsterdam and there were hoards of totally

indifferent Dutch people fishing and wondering what this strange ship was. Only in our imaginations were the

people on the quayside aware of who or what we were and why we were there.

Literally we were met without very much excitement at all. The South Ship was

already tied up. It must have been there a couple of days; there was nobody

around, they'd all gone.

We were paid off on the quayside and we were told that

we'd be kept informed as to what was happening. Of course we were not. I think it was generally accepted

that as far as Caroline was concerned that was it, there wasn't any future in

it. So very rapidly everybody went

their own way. I came back on a

flight with the Caroline representative whose job it was to pay people. He was based in London, probably something

to do with Major Minor; I can't remember his name. Don Allen followed a couple of days later. Jimmy Gordon became Guy Blackmore and

did a few shows for Radio One. Lord Charles Brown faded into oblivion. Ross Brown I think probably went back

to Australia to get his shorts laundered.

About a month after I'd finished on Caroline, I joined Harlech

Television.

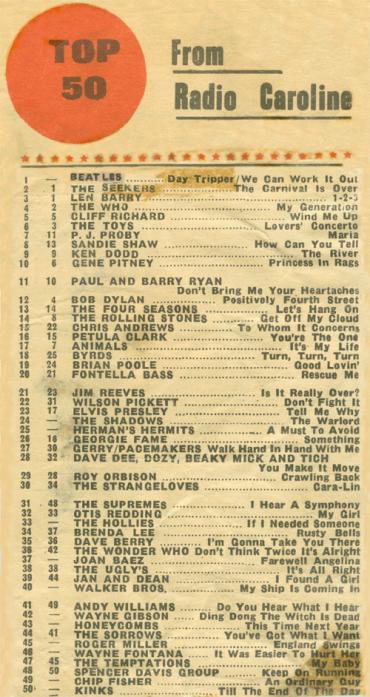

Radio Caroline ”Sound of 65” for

December 5th, 1965 courtesy of Music Echo

ADDENDUM: THE

CARL THOMSON STORY

From Happy Birthday Radio Caroline 20 years old

Easter 1984 produced by Monitor Magazine.

I

was working in the test department of Marconi Marine when one day a guy by the

name of Stan Fisher came down to me and said "Do you want another job? Someone's

looking for engineers for the radio station." It was Radio Atlanta, then.

So on the way home one night I called in on this guy at Billericay - he was a

radio amateur who's since gone to New Zealand - and had an interview. He fixed

up another interview for me with the Chief Engineer at the agents which was

down at Parkestone Quay. So I drove to Harwich to see Mr Gillman, an ex-BBC

engineer who came from Devon. He said he'd employ me so I left Marconi Marine.

It must have been around the beginning of 1965 the

first morning I reported to Parkestone Quay. There were Patrick Starling;

Richard, a courier from London, and myself going out on Offshore II that day;

the forecast was force six or seven; but the Offshore II was going to sail. So

out of Harwich harbour we go - and ten minutes later I'm sick over the side and

wondering what the devil I'm doing going out to this ship. It was a slow boat,

took about an hour and a half to get us there, and after an hour I was sick, I

was green, and I was wet because there was no shelter - you had to stay in the

air all the time. if you went down below the smell of Dutch tobacco used to

make you retch.

Finally we got on board. I was greeted by two other

engineers, an ex-Navy man who was on the point of leaving, and Trevor. At that

time the actual Chief Engineer was Ted Walters. He comes from Averly. Under him

was George Saunders, under George was Trevor Grantham, and then I joined. In

those days there were always two engineers on board. The guy I was relieving

was going to stay overnight to show me the ropes; they said "Have a lay

down for a couple of hours then we'll show you what's going to happen." We

were on 10 kW at that time and they were trying to get us onto 20kW through a

combiner.

Aboard the Mi Amigo

Starting at the bow there was the actual fo'c'sle head

which was just a paint store. Then you had the mast and the transmitter

lead-in, which was through the hold. There was a doorway entrance that went

down into the transmitter room in the hold. Next along was the studio which

used Gates turntables and desk. Then they had another small editing studio

because at that time they used to produce a lot of their commercials on board.

Then we had the dining room-cum- television room-cum - general sitting and

chatting room, then an area where there were some toilets and a stairwell that

went down to some cabins. Just after the toilets was the galley, there was a

bit of space which was the engine room fanlight, and then there was the crew

quarters aft. We used to live in the centre section and leave the crew alone

aft. If you went downstairs you hit your head against the bottom as you went

down; you had to remember to duck your head. As soon as you got to the bottom

of the stairs, you had to turn back and come for'ard. The first cabin on the

port side was Tony Visscher's, the Chief Engineer for the diesels. He came from

Amsterdam. Along on the port side was a two-berth cabin where the jocks were,

and a two-berth cabin for the cook. On the right-hand side there was another two-berth

cabin which was the Chief Radio Engineer's. I found out that it suffered from a

disadvantage that if you got a heavy-footed jock coming down the stairs when

you'd been on watch all night he used to wake you up; so we used to have a go

at a lot of jocks in those days! There was another two-berth cab in, then you

went into a room which was our library cum a place where you could meet. There

was a round table in there, there were the records, and there was a

transcription deck so we could play any records we wanted; and we had our

fridge in there where we used to keep our drinks. We used to get twelve beers

and twenty-four soft drinks a week, and we were allowed I think a hundred

cigarettes free of charge - after that you could buy more. Alongside that there

was a four-berth cabin and that was where I was assigned for the first time. I

soon had enough of bunking in that four-berth cabin! Between that room and the

forward transmitter room were the big water tanks, so there was a bit of

separation between the noise of the air from the transmitters and the sleeping

accomodation. The ship was originally a sailing bulk carrier made of iron and

when Radio Nord in Sweden took it over they cut it in half and put in a centre

section of steel. An electrolytic reaction was literally rotting the steel; the

old iron that they built in 1921 wasn't going to go, but the steel was going.

That was the Mi Amigo and that was home for me until I left in May 1967.

We had just one companion there, the Galaxy. The

Offshore I used to go to the Galaxy first and then to us, or to us first

depending on who had the crew change. But they always used to eat over at our

place because we had the better cook! The cooks varied; they were on six weeks

and about two weeks off. One of the Wijsmullers ran a company called Redwings,

they would do anything to do with the sea, and they supplied the crew, as well

as the fuel and all the bits and pieces; we drew all our stores from Holland.

Redwings put one Captain on board the Galaxy, Radio London, with a relief, and

they kept the same Captain, but with Caroline they used to alternate their

Captains on a rota basis and we would see maybe the one Captain for about six

weeks and then we'd see another one; you may pick the same one up after six

weeks or you may go three months and then he'd come back. Some of the Captains

on the South Ship were also Captains on the North Ship. They used to rotate

them, and they'd go off and do other work.

The Captain was responsible for the safety of everyone

on board and as such he would allocate where you were, to know how many people

he had on board. It was very hard to have people come out. If they came on

board it had to be official through Harwich; that was really strictly

controlled. Other than those people we rescued, there was never anybody

unofficial on board, that was absolutely forbidden. The Captain would even

allocate your cabin. There was a story - and it is hearsay - that when Simon

Dee walked on board and said "I'm Simon Dee, I'm the Disc Jockey”

the Captain said "Oh yeah? Your cabin's for'ard." Well there was one

cabin in the fo'c'sle down by the chainlocker and it was terrible - and he

stayed there for about four months before the Old Man moved him from that bunk.

The one thing I remember about Captain de Vrie was he was the one who loved

curry powder. He was getting on for sixty at the time, he was an old Captain

who'd sailed around Indonesia and he had curry powder with everything!

The Captain was responsible right up to the end, but

there was a lot of emphasis put on the Chief Jock and the Chief Radio Engineer.

The Chief Jock looked after the jocks but he always had to look to the Chief

Radio Engineer for, shall we say, disciplinary matters, if he had any problems.

If the Radio Engineer said somebody had to get off then he had to get off and

that was that. He had the authority from Chesterfield Gardens to do that; they

believed the Radio Engineer was a little bit more sensible.The actual programme

content, though, was always the Chief Jock's responsibility entirely.

The Merger had taken place when I joined but the

Atlanta crew was still there. The merger was for commercial reasons. Ainsley

and his backers still ran Radio Atlanta, called Caroline South, and Ronan ran

the North ship. I got into the routine of going out for two weeks on and two

weeks off and got used to the job. Not much really happened, it was sort of

maintenance; the only problem we used to get was the jocks letting go of their

Coke into the machines, that George Saunders, who was out there when I joined,

left soon after we beached. He was a technical writer for Marconi’s-Ted

Walters was very good. He used to build model steam engines. He used to spend

his spare time offshore using the lathe in the engine room for turning hub castings.

On the North Ship was Manfred Sommers, the Austrian. He was on all the time. he

didn’t seem to want to go home. Barry Wright was a guy who designed

triggers for nuclear things! Phil Perkins is a radio amateur. Bill Glendening

is dead now. He designed the suitcase transmitters for the agents during the

war. Pearsons didn’t stay with us very long. He was a young kid; about

sixteen. Trevor Grantham was there when I joined. He stayed; and worked on.

There were some more that came on-and-off. Barry Goldborn was one; another was

Ullamayer, he was a Hungarian, sort of thing. We were still trying to get the

combiner to work; we finally did get it going but it was a long job. We

couldn't get it to perform properly because the aerial resistance was lower

than anticipated. And then the Merger suddenly became complete. The people that

owned Atlanta dropped out and the Caroline staff came more onto the scene. We

suddenly-found we were on two weeks and off one; which was a little bit

tighter, but the money was put up a little bit so we didn't mind that too much.

I started off at £25 per week and when I left in sixty-seven I was on

£80 per week(when I left Marconi's I was on £10 a week). We were

classed as self-employed and I went on to self-employed tax which was a lot

better than PAYE. I paid an accountant six guineas and that was the best six

guineas I ever spent; he looked after my affairs all the time I was out there.

The Beaching

I was on board the night we came up on the beach.

Having switched off the transmitter at the end of programmes for the day at

eight o'clock, I'd been doing a bit of maintenance on the galley stove and the

motion felt funny. I'd been on there just less than a year and the motion was

different to what we used to get. Normally when we were in a gale the bow used

to dip down, she used to come up and then there used to be a 'wallop' as she

pulled the chain, then she used to stop, and you used to start diving again

immediately. At about eight-thirty that night she came up, there was a crack,

and she kept going.

The old Captain came forward and had a look, and the

chain looked alright. We had a good mile of heavy duty chain down and it looked

OK, He took a few bearings over half an hour and apparently we weren't moving.

Then the tide turned.

At about nine o'clock, the TV picture kept needing

adjusting. There was a rotator to keep the TV aerial pointing to the TV

station, and the jocks had to keep getting up to adjust the position of the

aerial. Then the Old Man took some more bearings and suddenly we noticed we

weren't really in position. Then the devil broke loose. Everybody started to

run around; we were looking at the chain and it looked taut, but we weren't in

the position we were supposed to be. The Old Man came in to me and said "I

think you'd better get everybody up." Then we drifted up towards Clacton,

and we came back down towards Walton, and the coast was getting rather close.

We were nearly on the beach when they started the engines,

and they wouldn't hold. There was too much rubbish around the propellers at

that time; she'd been laying there and they hadn't cleaned the weed from the

propellers. So they got the engines started but it wasn't any good, it couldn't

hold us. We started to come up on the beach rather fast. Suddenly the beach was

there; we came up and the seas were breaking over.

If you ever go down to Holland-on Sea and walk along

the sea-wall to have a look, you'll find that all the way along there are

groynes that act as breakwaters. The

Mi Amigo's length is about one hundred and eighty-seven feet, am the

groynes were going out at one hundred and fifty feet spacing - except for one

place where they had a cement structure that was an old war-time jetty. There

there was two hundred and something feet, and we beached her up there. Just

parked it nicely. Nobody had anything to do with it at all; Someone was looking

after us that night.

We came up, then Tony Visscher said "get

down" because they started firing the rocket-gun for the rescue lines to

come over. One of them hit the side structure, another one hit us close to a

window, but finally one of them got a line over and they put the breeches buoy

on board. We all went up aft just underneath the bridge and we started to get

the jocks off.

The Senior Radio Engineer on board was in charge of

the whole of the English crew, the jocks and the radio engineer. At that time

George Saunders was the Chief Engineer on that particular shift, although he

was a lot younger than I was. While they were being got off I suddenly

remembered the closing theme which was by Jimmy McGriff. I believed that there

was only one copy of that; it was scratched but it was the only one we had on

board and I thought we couldn't get another one from London. So I tucked it in

my shirt. I'd already been down earlier and got some warm clothing, and taken

the crystals out of the transmitter.

In the rush, George and myself had forgotten to put

the covers over the top of the air vents to stop the seas from going down into

the top of the transmitters. Later, when we spoke to Ted Walters, the first

question he asked was about the covers. The answer didn't half make him

unhappy! Its the only time I ever got a rollicking from him.

I told the Old Man that all the English personnel were

off and he said "You must go ashore", and then I went ashore in the

breeches buoy. I'd only got my slippers on. By the time I landed on the beach

my trousers were soaking, I'd lost my slippers and I'd lost my socks. As I was

walking up the beach I thought "We must be famous, they've even laid the

red carpet out, I can't feel the stones". It wasn't until I'd scrambled up

to the top and looked down with the headlights of the ambulances, I saw it was

so soft because I'd been walking on six inches of snow! Carl's toes turned

blue, and I actually got frostbite that night.

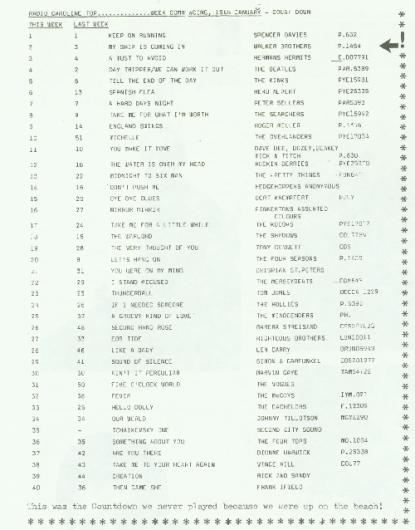

Radio Caroline

”Countdown of Sound” never played on the South ship because the Mi

Amigo went aground. From Carl Thomson’s collection. From Happy

Birthday Radio Caroline 20 years old Easter 1984 produced by Monitor Magazine.

We came up to the nearest place in Frinton; I think it

was the Golf Club. First person to greet us: British Customs! "Anything to

declare?" So I took my cigarettes that were all wet and soggy, "Yes!",

straight into his hand-said "Oh, thank you very much, sir!" and threw

them down. The Customs were only there for a minute, then the Lifeboat

secretary and the Coastguard staff took over and did all the arrangements, and

they got a hotel opened up. First of all they took us round to a store. As we

were distressed seamen we could get some dry clothes out of this store and I

got shirt, a pair of jeans, a woollen jumper, some socks and some plimsoles.

The jeans I wore for about fifteen years! They were blooming good quality that

we got free of charge that night. I've still got the jumper somewhere too!

They took us to a hotel, and that hotel room was cold.

The manageress who was running the place said "I'll make you a nice cup of

tea" but we said "We're residents here, aren't we? Open the bar!

Someone will pay in the morning", and we had double Scotch, and brandy,

all round, and that made the pain go away. By the time we went to bed my toes

were really aching but in the morning they transferred us to Harwich where they

had a look at them, and they were alright.

I got mentioned in the press that day! I think this

was from the old "Express": "Ashore, cold and soaked, came Dutch

Steward Thys Spyker, nineteen, radio engineer Carl Thomson, twenty-three, chief

radio engineer George Saunders twenty-four, audio technician Patrick Starling

and disc jockeys David Travers, twenty, Thomas Lodge, twenty-five, Graham Webb,

twenty-nine. Tony Blackburn, twenty-three and Norman St.John. Lifeboatman John

Hall said after the rescue: 'The disc jockeys were laughing and waving pictures

of girls when they reached the beach. They seemed cheerful." Tom Lodge was

the first one that came ashore. That cabin boy was wrecked twice in one week!

We reckon he was the Jonah! Only a few days before, the "Galaxy" had

gone adrift. They didn't beach, they were lucky in that there was a tug around.

We'd laughed at her because she went right into the Limits, she was nearly up

in West Mersey. When they towed her back we were all laughing and generally

joking. Thys was on Radio London then, and he transferred over to us because we

were short-staffed. He didn't come back after that.

I went back on board the Mi Amigo the following day at

low water and hung around when they got her off. We discovered the reason why

the chain was straight - it was broken at the anchor and we still had all the

chain down. was so rough that it needed that final grip to hold it. That was

the reason we were moving about so slowly we never realised we were going.

Weismullers tug Titan came over from Holland and put a

line on board. He had two miles of line on to get a tow because he couldn't

come in over the sands. They used a small boat to bring the line from the Titan

to the Mi Amigo fixed it to the bow. If you look on a chart, the only wreck for

miles is that of a fishing boat. On the first pull, they got tangled in that

wreck and the line broke. The next night they ran the line in again and got her

off. We actually wrecked our engines getting off the beach - our main engines,

not the generators. We had a small generator a big one. When we came up on the

beach we shut down the generators; but they worked off the small generator that

only gave emergency lighting and compressed air. When they started to tow; Tony

Visscher started the engines and they wopped it at "ahead". For about

four minutes they gave just that extra impetus to get the Mi Amigo off the

beach; but she took in so much sand that it just wrecked all the liners on the

pistons. The sand blocked up all the cooling water; too; and everything

overheated and she seized. But; they got her off; and she went out and anchored

in the Gunfleet.

Mi Amigo goes to Holland

I and Patrick Starling, who was a studio tech employed

to look after the studios, said we'd go with her to look after the engineering

side. So; we were going to Holland with her; and off we went. The Offshore II

took us to the Mi Amigo; and the Titan towed the Mi Amigo to Holland. Both the

Offshores I and II remained in Harwich.

We couldn't do much except help the cook. On the first

day; however; I used the opportunity to give the transmitters and the

transmitter room a good clean out. Patrick cleaned and checked the studio, When

I got up the next morning there was grease and oil all over the clean

transmitter room and some of the pumps were running: we'd sprung a leak

underneath the water tanks. It was the steel section of the hull. The iron was

alright but the modern steel had gone and we were making water in there. So

they had the pumps running all the time from then on; until we got into

Holland.

We went into Ijmuiden; and Ijmuiden is one of the high

points in Holland.Theres a hill up on the starboard side as you go in through

the lock. Well; it had been announced that Caroline was coming in on Radio

Hilversum - and I've never seen so many people in all my life. That hill was

black with people when we came into Holland. It was about five o'clock at night

when we finally made the harbour entrance and all over the hill it was just a

sea of bodies like ants. They'd come from all over Holland to see us. We went

in the locks and up toZaandam where we stayed for a good while.

That's when we hired the Cheetah for a period of time,

Cheetah II arrives

The Dutch Authorities were; shall we say,

"nervous" about having transmitters on the ship in Holland. When I

came back the next time (we were still on our two weeks on / two weeks off

period) they'd already lifted off the transmitters and they were in bond. The

Cheetah, from Radio Syd, was FM only, so what we did was to load one of our

transmitters onto the Offshore I; take it over, and

lift it on board the Cheetah and fit it out in one of the holds. We used a wire

aerial which was nothing fancy; it was just a piece of wire up to the highest

point on the mast and then back to a stay. I suppose we were getting 6kW into

the thing; if we got 10kW we used to arc over like the Devil. But at least it

brought Caroline's name back onto the air. We used the original studio of the

Cheetah.

The 201 metre crystals stayed with me right up to the

time we brought Cheetah on the air; I actually put them back in. They were

large; glass crystals in valve sockets; so they were wrapped up in cotton wool.

They were in my soap bag; in my shaving kit; the whole time; and were never

found. The Jimmy McGriff record had been handed over to the office in London;

it went out to the Cheetah and was transferred back again to the Mi Amigo.

We were broadcasting from the Cheetah within about

four days of getting the transmitter in. All of the jocks came out; they just

picked up their rota and continued. On the engineering staff; Ted Walters,

Trevor Grantham and Patrick Starling

all came out at some time. We all came out on the tender just as on a

normal shift.

One night when I was at home I suddenly got a call to

say that the Cheetah was going to Lowestoft! What had happened was, one of the

dirty water dischargers for the toilets was so old it'd broken, and as it was

below the water-line it was letting in scawater. They managed to get somebody

to seal it off from the outside, then she had to come to Lowestoft, where they

repaired this outflow at Richards Yards. I sailed on her from Lowestoft down

the coast to the anchorage, then we started rebroadcasting.

I got on well with the tugboat crews. The tug that

helped her up from Lowestoft came from Harwich on a Sunday, and I passed a

crate of beer over to the tug for their lunch. Ever afterwards, if they

couldn't get a tender and this tug came out in place of the Offshore I, they always

remembered me and I always got a cup of tea from them!

So the Cheetah went on, and slowly people began to

leave. Trevor went to pastures new for a time, George left; and that left Ted;

myself and some new ones. Then Ted left and I came up into the Chief Engineer's

position on the Southern Ship.

I wasn't on the Mi Amigo on the day she sailed back

from Holland because it was my shift off. The engineer on there was Paul Dale.

The new 50kW transmitter came on board in boxes in Holland and it was fitted on

the tow. The new layout; as you came down the stairs, was the Ten directly

opposite to you and on the right was the Fifty in four

cabinets with all its meters and dials. At the bottom

of the stairs we had a little cabinet with all the monitoring in, the

modulation meter; the compressor, the monitor 'scope and the patch-panel. So as

you came down the stairs you could check the modulation as you went in. It was

the spare Ten that was over in Holland that went on board the Mi Amigo; the Ten

that was on the Cheetah went, I think; to the North Ship as a spare.

The Ten was a Devil of a job to get on. We'd lost the

connection diagram and were trying to work out the phasing of the 'delta'. The

HT transformer was three separate transformers with three windings and you had

to phase them up; on the actual 'delta' winding you had to get the phasing

right all the way round. There were six connections so you'd got all the

permutations of any six with any six and it took us ages to work it all out how

they went. We'd bring the generator on; switch on; and "Bang!" off

would go the 200 Amp mains fuse. We went through fuse after fuse but we got it

right in the end.

Mi Amigo returns

When we came back with the high power I think we

literally took Radio London to the cleaners. It all settled down into a period

when the Southern Ship was making number one in popularity charts all the time.

Bill Hearne was a Canadian who became programme director. He was the one who

brought us Caroline Cash Casino and that was a winner; that paid for the 50kW

transmitter.

We had transmitter serial number Fourteen from

Continental Electronics. We were due to get number Twelve; but it was at the

time of the Rhodesian UDI and the U.K. Government set up a station in Botswana to

broadcast into Rhodesia. So they bought numbers Twelve and Thirteen and we had

number Fourteen. It was a very good transmitter, very reliable. They wanted to

try and improve the aerial system and they had erected some sort of wire

aerial. Every time they started to fire up they had sparking off this wire. I

was looking after Cheetah's transmitter and went over to look at Caroline with

Tony Blackburn and everybody else. That's the time Tony went up the mast; but

that's another story. We then brought the 50kW on and ran it for forty-eight

hours - and suddenly all the lights went dim as the big new generator coughed;

spluttered and slowed. We went into the transmitter hall and it was full of

black; acrid smoke. So I slid down the stairs to the transmitter and hit the

'off' button on the HT - and I blew every light-bulb that was on at the time on

the Mi Amigo. They just went bright and went out. This was because when we lost

the full load; the generator just raced away, the volts went up, and none of

the stabilizers could take care of it because the generator was too quick for

them. The HT transformer was faulty from new. We'd lost that and had to send

back to the States for a new one. When we got a new one back we were OK.

On the Cheetah we were only running eighteen hours a

day so there was a period in the middle of the night when we were testing on

259. Then we took the transmissions from the Mi Amigo. There was a portable

receiver over on the Cheetah; something with a very small; directional aerial;

it was put in a position by a window behind a metal panel and that kept the

main transmitter virtually out. We took an output off the audio stage; matched

it into one of the mixer ports in the studio on the Cheetah; and that was fed

into the transmitter. We fed into a mixer panel so that the Cheetah could fade

out the portable and take over its own broadcasts at any time; but it was never

needed.

When we started to run the 50kW transmitter we had a

problem because of the mast. It was quite a good mast; designed and built in

Cowes by Harry Spence . But the insulators on the mast weren't designed for

50kW and were arcing over. They seemed to arc and discharge into the sky. I was

out there by myself; one day when there weren't two engineers at the time; I'd

worked the morning shift and been up doing maintenance since about three

o’clock. After lunch; at about one o'clock; I thought I'd go down to my

cabin and get my head down. At one o'clock they'd change over; DLT went out

with his theme music "A Touch of Brass" - a nice quiet song - and

Rosko came on with his theme; a thumping "Memphis" sound. So just

before I left the transmitter I thought "Rosko's on in a minute; I'll give

it a couple of dB's more on the compressor" and set it up.

I'd just taken my trousers off to lie down to have my

afternoon nap when Crash! Bang! Thump; thump; thump down the stairs;

"Carl! Carl! where's the engineer?" I came out and on the stairs is

Tony Prince. He'd been sunbathing; and before this he was bronze - today he was

white from head to foot; with fright! "The Mast's alight!" Up the

stairs I go; out onto the deck; look up into the mast - and from every

insulator from the very top to the very bottom in tune with "Memphis"

there were sparks going out into the atmosphere! So I went down; pressed the

button; switched it off; put a few more dBs in and brought Rosko back in at a

little bit lower power. Then we sent an urgent message ashore and

"C&S" came out and put bigger insulators on the mast. When they

took down some of the stays; which were multistrand wires about an inch and a

half in diameter; the RF had actually eaten through a lot of them and they were

holding on by one or two strands. We only just caught it; it was the only time

it happened but we didn't need it to happen!

The riggers came out in a gale and went up that mast

changing the stays in wellie boots and sou'westers. The Chief; who went right

up to the very top to direct it; was sixty-five and they'd called him back from

retirement. He was showing the young kids how to walk across the mast - he had

no safety harness and she was rolling. We had to go off the air when they were

changing the stays; I asked "How long will you be?" He said

"Once we're over that insulator you can switch back on again;" and

they were quite OK; no problem. They used the same bits of the mast; and just

modified it to fit where they put the new insulators.

The original aerial was a folded dipole which had

nulls going out into France; and up the country (the North ship was supposed to

cover that area); when we were laying with the tidal stream. It was a very

shallow null; not as deep as people thought; but if the tide was turning the

signal used to drop; and you could lose it up in London. Then we had some

complaints from the advertisers;

but we used to turn in twenty minutes so it wasn't for long. At the same time

as fitting the 50kW we went over from a folded dipole to a base-loaded antenna.

At the point in the sky where you see it cut off they put an insulator in and

the rest of the mast sat on top of that. That was the piece that was actually

radiating; less than a quarter-wave; vertical. There was a loading coil up

there which worked pretty well. It was a good aerial; but I personally would

have liked to have tried the folded dipole with the 50kW.

The only fault that we found on the 50kW was that; to

start off with; we couldn't load it to full power; she went unstable; and we

lost a lot of screen grid decoupling capacitors trying to solve this problem.

The screen grid decoupling capacitor was a Teflon ring between the valve base

and the chassis; the ceramic valve sat down in this ring. We doubled up on our

Teflon rings to get a bit more protection because we used to get a salt-water

build-up over the edge of the ring and then that was it; gone. Then Radio

England came on the scene. The Yanks came over to teach us how to do it; and

they had no end of trouble. They had about one ohm impedance at the base of the

aerial and they just couldn't hold the thing. They had to bring over the guy

from Continental Electronics; Joseph B. Sainton; an interesting character who

had survived the Boeing 707 that caught fire and smashed up at Rome airport in

the early Sixties. He was on the tender and just happened to step aboard our

ship. He traced the problem and added some more screening decouplers on the

P.A. valves; we could then load the full fifty without all the problems we'd

been getting.

We used to get occasional flash-overs. I remember one

night. We didn't move about a lot normally but this night we were in a gale

situation. We were moving around quite a bit and as the mast swung with the

motion of the Mi Amigo the impedance would change; the VSWR would go up; then

the H.T. would lock out. We had a lockout relay; with four positions; it would

switch the H.T. off; come back on again; if the fault was still there switch

the H.T. off again; take four tries and if on the fourth try the fault was

still there then the relay would drop out completely; deactivate a solenoid and

switch the H.T. off. There was also a safety rod that would go over so that if

there was any charge on the H.T. capacitors it would "crowbar" and

discharge the capacitors. That used to go off with a wallop.

The stairs came down the side of the transmitter hall;

and our little watch-keeping room was under the stairs. About two o'clock in

the morning you could put your feet up and doze there nicely. So Carl is in his

chair and he didn't hear the first one; couldn't have done; I swear to this day

I counted three. We used to count the clicks and if it got to the third one you

used to go and hit the H.T.and bring it off normally. The first one must have

happened while I was dozing. The fault didn't clear; I heard "Click...

Click..." and I thought the third one was coming; but then there was a hell

of a "Bang!" as the thing went off; and I fell out of my chair! This

bang used to wake you up; it was 16kV at four amps; there was a hell of a lot

of charge in those capacitors. Coming out of sleep I wondered what the devil

had happened.

What had happened was that in the gale the

phosphor-bronze lead-in at the bottom of the aerial had worked loose and broken

adrift. It was actually swinging around in the gale. We modified it and were

back on the air within about half an hour. Then I spent the night out with arc

lights re-routing the damn thing to take the strain off it so that it couldn't

happen again.

All of our maintenance was done during the night. We

used to work a six hour period; come off for six hours; go back on duty for six

hours. If we were running twenty-four hours we'd do the maintenance work about

three or four in the morning. There were always two men on watch from about

eleven o'clock Sunday night until five o'clock Monday morning; and that's when

we had all our studio maintenance; we had a six-hour period when we were

completely off the air and that's when we used to do all the work and any

modifications we wanted to do. On Mondays it was engineers crew change. The guy

who was leaving the ship would be the one who was going on nights; and the guy

who was going onto nights would have to work part of the afternoon and the

Sunday night through to Monday morning. He'd hold the fort until the guy coning

on started his watch; then he'd go to bed ready for his night-shift. The guy

coming on board would start off on days and the next week would go onto nights.

The weeks I was off I had to call into Chesterfield Gardens;

I suppose I went up twice a week; once when I came off

and again before I went back. The ships were virtually autonomous as far as the

running of the technical side. If we were off the air; which was very

infrequently; then they would want to know the reason why. They used to have

speakers up in Chesterfied Gardens and the minute it went off in the daytime -

not in the middle of the night! - Ronan used to ring Bill Scaddon and a message

would come out the next day calling for an explanation.

Before the full merger there were two chief engineers;

both in London; and a sort of foreman out on each ship. When it became Caroline

overall; once Mr. Gilmer had gone - he was past retiring age anyway - Paul Dale

took over in London. His function really was an administrator and to advise

Ronan who was always in the office running the show. After a time I got the job

of looking after both of the ships; I was a sort of travelling chief; working

so much on the South ship and then I would go up and have a look at the North

ship. Manfred Sommers was the chief engineer up there so I had to go and take

his reports and do bits and pieces with him. We were flying up to Ramsey in the

Isle of Man by Cambrian Airways at the time. We used to fly Heathrow, sometimes